Watchmaking is anachronism transformed into art.

It is the art of utilizing plenty of inventiveness, of technique, of savoir-faire; it is extracting the quintessence of the engineers and watchmakers' work to compose odes to uselessness.

When one writes that a watch is paradoxical, it is always flattering, as paradox is one of the pillars of uchronisme.

Yet, the Breguet 7047 is probably the most uchronic piece in watchmaking.

Stylistically, it is an anachronism, because it pays tribute (I insist on this word, which is not sullied in this context) to a style which disappeared with French watchmaking, the style of the Breguet subscription watches, a style which in certain ways was already very urban and super-modern based on the 19th century criteria, opposite to a certain Helvetian bucolism.

But it is also horologically uchronic; it is the overlapping of Middle Ages with Cyberpunk:

In 1490, Leonardo Da Vinci invents the concept of the Fusee-chain (at this time made with gut cord).

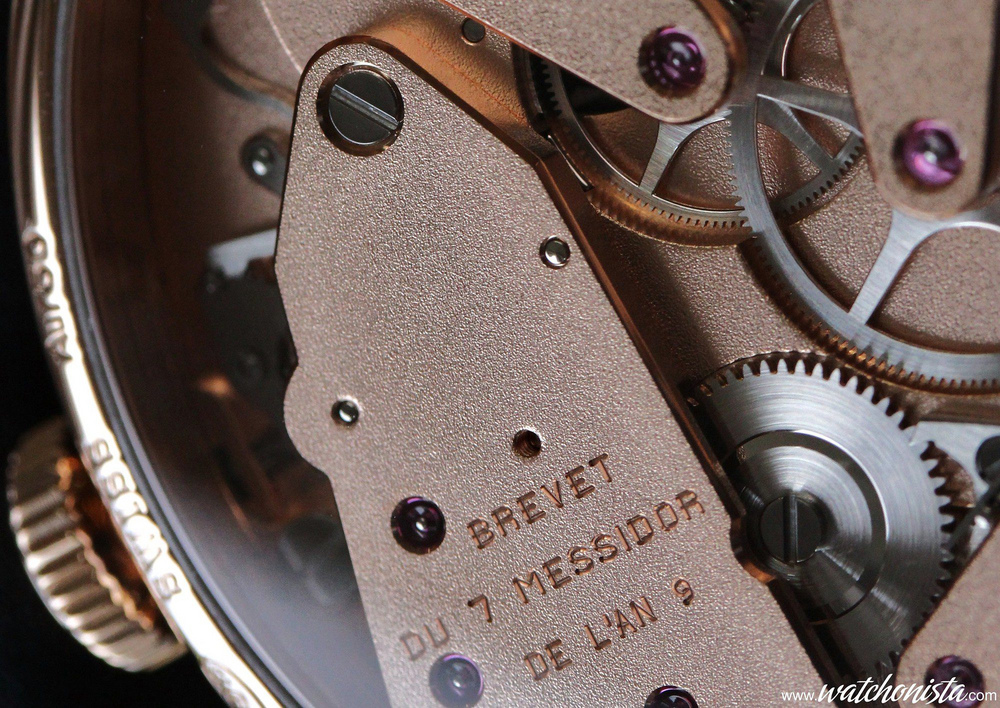

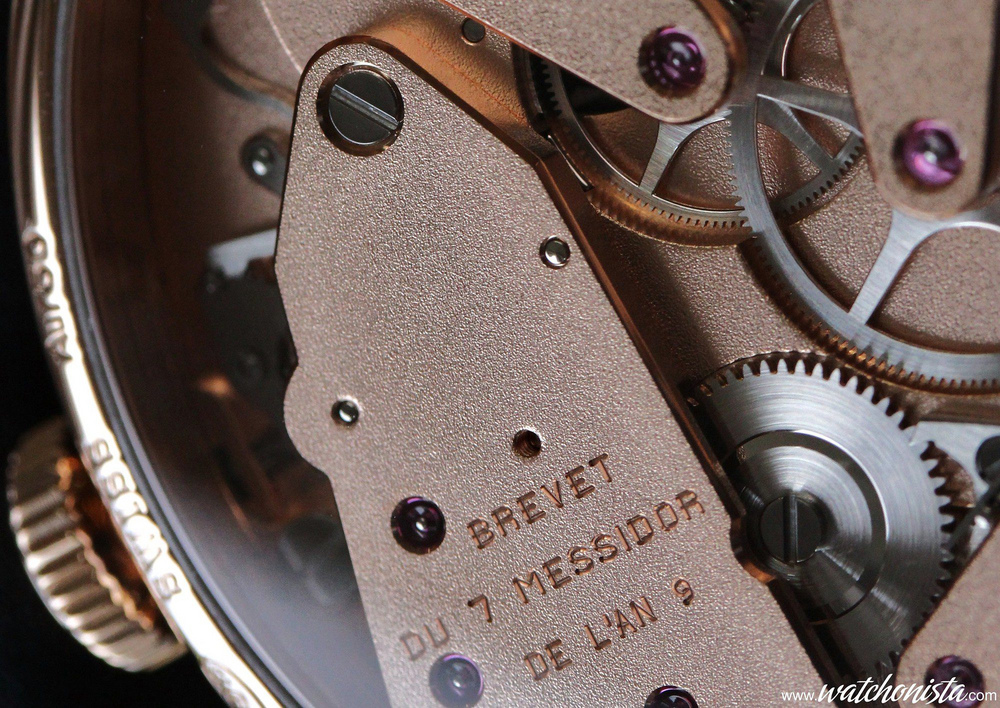

-Around 1790, A.L Breguet invents the Tourbillon and patents it on June 26, 1801, namely Messidor 7th, Year IX of the French revolution calendar.

-In 2000, the watchmaking industry starts to put silicon in the movements (Nivarox, Ulysse Nardin, and De Bethune).

During the Renaissance, springs are prehistoric, the periodic table has not even been thought of, the modern steel industry is in its infancy and alchemy is considered a science. The Fusee-chain allows for the regulation of the "home- made" springs broad variations, akin to the derailleur of a bike: the increasing fusee diameter (the "3D" wheel) compensates for the chain loss of tension, keeping it steady. But with the renewal brought by the Enlightenment, the metal industry improves dramatically and springs become far more reliable... In 1770, Jean-Antoine Lepine notices that they are of a quality good enough to get rid of the Fusee-chain; hence, he creates the modern layout caliber, with a plate and bridges.

During the turmoil of the French Revolution, Abraham-Louis Breguet patents the Tourbillon. There may be doubts regarding his motives: was he trying to find a better way to lubricate the mechanism? Did he want to improve chronometric performances by allowing the escapement to be mobile? This is the most commonly accepted hypothesis, as at this time, watches were carried vertically and gravity weighed on the escapement.

Like the Fusee-chain, the tourbillon became somewhat outdated. On the one hand because of the advent of the wristwatch, allowing for multiple positions, and on the other hand because of industrialization, which replaced the work of the best setters by assembly lines of standardized movements.

At the turn of the 2000's came the advent of silicon; neither metal nor plastic, this synthetic material is designed to push the envelope of the laws of physics, which had been limited at the start of watchmaking due to the lack of consistency and the weight of the alloys employed.

A revolutionary technology to some, the death knell of traditional watchmaking to others, in any event, silicon is an endless source of polemics...

This Breguet Tradition 7047 is thus at the apex of the watchmaking paradox: indeed, it synthesizes medieval technology, the Fine watchmaking tradition and the mechanical horology post-modernism.

But it is also an uncomplicated watch featuring a grand complication!

Except for the power reserve...Indeed, only the extra functionalities or displays are considered as complications by watchmaking orthodoxy. But the improvements of the power chain, regarding the escapement (in this case the tourbillon) as well as the barrel torque (thus the Fusee-chain) are not complications stricto sensu. Yet, the development of the caliber with its hundreds (????) of parts, its 43 jewels and its machining relying on state-of-the-art technologies (especially the hairspring) reach a level of complexity never seen until now. Therefore, this watch is "complex" but not "complicated".

The 7047 is super-demonstrative, the path of the chain is fascinating and the rotation of its One-minute tourbillon is mesmerizing. For that matter, the chain is far bigger than the competitors' and perfectly resonates with the large silicon balance (13mm) and the very large (17mm) titanium tourbillon carriage. The overall color in gray tones is in good taste, and perfectly matches the very clean and very rough sand-blasted finish. It is the opposite of a first communion watch. One can even go further by saying that it is different from the dominant style in the high-end market. When it takes a magnifier to appreciate the bevelings of a Dufour, here, one has to look at the watch from a distance, as the design is so brutal. While it is not "showy", it nonetheless impresses at first sight, it is impossible not to notice it.

The specificity of this version is that, akin to the Breguet Tradition 7057 without tourbillon, its bridges are red gold coated. In my opinion, it is the most suitable for this model, because the white gold version is too cold, the ruthenium version is too modern and the yellow gold version is too vintage. The red gold finish combines the vintage look of yellow gold and the dynamism of ruthenium. The warmth of red gold creates a contrast with the sharp bridges. The caseback is the most beautiful of the "Tradition" collection. And it is probably the most successful watch of the series: the 7027 was very nice, but a little too sober; the 7057 was funkier, but this 7047 is totally a beast! Here, Breguet did not try to do something cute. They tried to do something in the style of Abraham-Louis Breguet: everything is off centered, asymmetrical, the tourbillon uses as much room as the hour-dial, it is functionality before its time.

It is the art of utilizing plenty of inventiveness, of technique, of savoir-faire; it is extracting the quintessence of the engineers and watchmakers' work to compose odes to uselessness.

When one writes that a watch is paradoxical, it is always flattering, as paradox is one of the pillars of uchronisme.

Yet, the Breguet 7047 is probably the most uchronic piece in watchmaking.

Stylistically, it is an anachronism, because it pays tribute (I insist on this word, which is not sullied in this context) to a style which disappeared with French watchmaking, the style of the Breguet subscription watches, a style which in certain ways was already very urban and super-modern based on the 19th century criteria, opposite to a certain Helvetian bucolism.

But it is also horologically uchronic; it is the overlapping of Middle Ages with Cyberpunk:

In 1490, Leonardo Da Vinci invents the concept of the Fusee-chain (at this time made with gut cord).

-Around 1790, A.L Breguet invents the Tourbillon and patents it on June 26, 1801, namely Messidor 7th, Year IX of the French revolution calendar.

-In 2000, the watchmaking industry starts to put silicon in the movements (Nivarox, Ulysse Nardin, and De Bethune).

During the Renaissance, springs are prehistoric, the periodic table has not even been thought of, the modern steel industry is in its infancy and alchemy is considered a science. The Fusee-chain allows for the regulation of the "home- made" springs broad variations, akin to the derailleur of a bike: the increasing fusee diameter (the "3D" wheel) compensates for the chain loss of tension, keeping it steady. But with the renewal brought by the Enlightenment, the metal industry improves dramatically and springs become far more reliable... In 1770, Jean-Antoine Lepine notices that they are of a quality good enough to get rid of the Fusee-chain; hence, he creates the modern layout caliber, with a plate and bridges.

During the turmoil of the French Revolution, Abraham-Louis Breguet patents the Tourbillon. There may be doubts regarding his motives: was he trying to find a better way to lubricate the mechanism? Did he want to improve chronometric performances by allowing the escapement to be mobile? This is the most commonly accepted hypothesis, as at this time, watches were carried vertically and gravity weighed on the escapement.

Like the Fusee-chain, the tourbillon became somewhat outdated. On the one hand because of the advent of the wristwatch, allowing for multiple positions, and on the other hand because of industrialization, which replaced the work of the best setters by assembly lines of standardized movements.

At the turn of the 2000's came the advent of silicon; neither metal nor plastic, this synthetic material is designed to push the envelope of the laws of physics, which had been limited at the start of watchmaking due to the lack of consistency and the weight of the alloys employed.

A revolutionary technology to some, the death knell of traditional watchmaking to others, in any event, silicon is an endless source of polemics...

This Breguet Tradition 7047 is thus at the apex of the watchmaking paradox: indeed, it synthesizes medieval technology, the Fine watchmaking tradition and the mechanical horology post-modernism.

But it is also an uncomplicated watch featuring a grand complication!

Except for the power reserve...Indeed, only the extra functionalities or displays are considered as complications by watchmaking orthodoxy. But the improvements of the power chain, regarding the escapement (in this case the tourbillon) as well as the barrel torque (thus the Fusee-chain) are not complications stricto sensu. Yet, the development of the caliber with its hundreds (????) of parts, its 43 jewels and its machining relying on state-of-the-art technologies (especially the hairspring) reach a level of complexity never seen until now. Therefore, this watch is "complex" but not "complicated".

The 7047 is super-demonstrative, the path of the chain is fascinating and the rotation of its One-minute tourbillon is mesmerizing. For that matter, the chain is far bigger than the competitors' and perfectly resonates with the large silicon balance (13mm) and the very large (17mm) titanium tourbillon carriage. The overall color in gray tones is in good taste, and perfectly matches the very clean and very rough sand-blasted finish. It is the opposite of a first communion watch. One can even go further by saying that it is different from the dominant style in the high-end market. When it takes a magnifier to appreciate the bevelings of a Dufour, here, one has to look at the watch from a distance, as the design is so brutal. While it is not "showy", it nonetheless impresses at first sight, it is impossible not to notice it.

The specificity of this version is that, akin to the Breguet Tradition 7057 without tourbillon, its bridges are red gold coated. In my opinion, it is the most suitable for this model, because the white gold version is too cold, the ruthenium version is too modern and the yellow gold version is too vintage. The red gold finish combines the vintage look of yellow gold and the dynamism of ruthenium. The warmth of red gold creates a contrast with the sharp bridges. The caseback is the most beautiful of the "Tradition" collection. And it is probably the most successful watch of the series: the 7027 was very nice, but a little too sober; the 7057 was funkier, but this 7047 is totally a beast! Here, Breguet did not try to do something cute. They tried to do something in the style of Abraham-Louis Breguet: everything is off centered, asymmetrical, the tourbillon uses as much room as the hour-dial, it is functionality before its time.

Comment