Hello my friends,

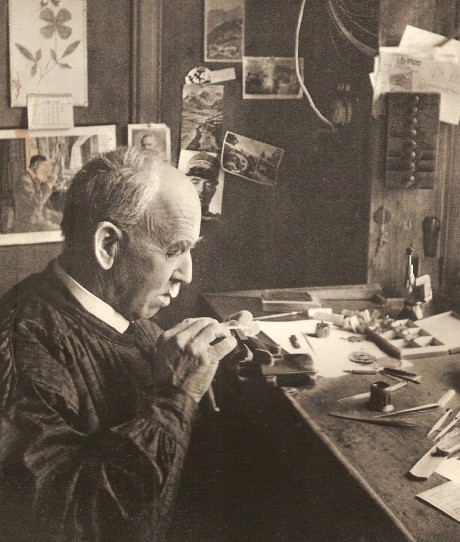

I was absent from the forum in past year, as I was working for a watchmaking company, for which I was involved in preserving know-how projects.

But I missed my blog activities! I don't feel I am cut off to sit behind a desk, so I created a new website:

www.foudroyante.com/en

Let's talk about watchmaking, without complacency, and also about history and know-how. Here is a condensed version of an article I wrote recently about the Farmer-watchmaker, from 1380 to the beginning of the « glorious thirties ».

In Europe, Roman Empire collapsed by the end of the 5th century, but it left behind a continent more united than ever, using a single language, Latin, and a single religion, catholic Christianity.

This unity led to one of the longest period of deadlock in European history: the middle ages. Its economy was based on the clearance of vast forests that covered the continent. In these conflictual times of relative stability, the population

grew until the end of forest cleaning, in 1280. Contemporary Europe was less wooded than it is today.

Celtic and Gallic agricultural skills had been forgotten and the yields were minor: between 5 and 10 quintals per hectare.

The current productivity in comparison is 80-100 quintals per hectare in intensive and 40-50 in organic. It was only in the 17th-18th century that Europe started its first agricultural revolution, with new techniques of crop rotation, accompanied by forage plants.

Doubling yield were translated into savings on labor, and feeding several generations of scientists. One of them was

Christian Huygens widely regarded as the inventor of modern watchmaking concepts. This will be the beginning of the industrial revolution.

Let us return to the 14th century, the darkest period in Middle Ages history, which unfortunately tends to provoke a skewed vision of that period, yet relatively prosperous and peaceful.

Poor crop yields were hardly sufficient to feed the increasing population. In addition, in the early 14th century, a series of years of drought followed by years of torrential rains caused widespread famine in Europe. Malnutrition was a fertile compost for diseases, especially for the terrible black plague.

The tensions related to the resources led to a war series, in particular the one hundred years war. To finance wars, taxes rose disproportionately, provoking violent jacqueries. It is thus in this particularly dark context that ended the 14th

century.

Imier De Ramstein, Prince-Bishop of Basel was elected in 1382. His bishopric included the Canton of current Jura. Its debt remained huge at that time. Imier made repeated attempts to boost the local economy. In 1384, he published a ery innovative edict: a tax exemption for those who settle 1000 meters above sea level.

Many farmers, by the end of the century, weakened by a hundred years of shortages, diseases and violence, set out to conquer an environment famous to be inhospitable, even hostile.

In the year of our Lord 1384, the Canton of Jura wasn't completely wild, as evidenced by the village of Montfaucon, built in the early 11th century.

However, the nature remained particularly wild, probably unchanged since the last glacial era. Wolves and bears reigned supreme over the fauna. The common point of these species is their adaptability in the conditions of height, thanks to their coat, their muscular power, their overdeveloped vascular network or their large-scale wings. If this fauna prospered, it was because Jura was protected for a long time from the human presence, thanks to a rough microclimate and to a steep topography.

In spite of a modest maximum height (1720 meters), the drafts and the high perched valleys cause very low temperatures during the winter : in the Vallée du Joux, or, even worst, in the vallée de la Brévine, the temperatures

Sometimes dip as low as -40°C.

Nowadays, Jura is divided between Switzerland and France. The wars made the border move, notably during the 30 years war (1618-1648) and also during the Napoleonic wars (1798-1815). The imperial desires of the French autocrats

Sometimes overflowed on the future territory of the Swiss Confederacy, the people from Jura have always shown themselves to be extremely supportive, especially in the Franches-montagnes, where contraband (notably watchmaking) was wisely organized.

But in 1384, our « Franc montagnard » had to become established. As he often does, man changed his environment and farmer-watchmaker ancestors organized vast slash-and-burn, in order to increase the building and arable surfaces.

That is how a multi-thousand-year-old forest of broad-leaved trees disappeared. The inhabitants of Jura planted coniferous trees which push away much faster in extreme montain conditions.

This choice of essences made them precursors of sustainable forestry exploitation. With a view to preservation, fences were forbidden in « Franches montagnes » by the Bishopric of Basel. That explains the presence of these magnificent demarcation low walls in the fields.

It should be pointed out that contrary to common beliefs, until the industrial revolution, serfs in traditional society did not work a lot, three days a week in average. The rest of the time was dedicated to parties or celebrations (religious or not), household activities, collection in the forest, handiwork and wine.

But the farmers of Jura had to work a lot more. In order to gather enough provisions to get through the cruel winter, the brief six month sunny season was a period of intense work. Thus, in the summer time, they had to get up even earlier for long days of agricultural labor: do the transhumance, plant and collect cereals, fruits and vegetables quickly, cut hay, and take refuge with the hearth before the snowfalls. The agro-sylvo-pastoral balance was particularly fragile in such a hostile context. Moderation, patience and precision were essential to the survival mountain farmers. They also needed those virtues for craft sector, and even more for watch-making.

From the beginning of the 15th century, the « Franc-montagnards » farmers knew the torments of contemporary work pattern, with the stress of a "deadline", literally!

At this beginning of the Renaissance, the leisure society was still distant. The future farmer-watchmaker were about to spend their winter time making crafts.

And as the constraint makes the man, they adapted their crafts to logistic constraints, in a typical Darwinian logic. It takes a daytime to walk 15km in the mountains. This difficulty of access weighed against any manufactured product of consequent size, so they specialized in small accessories with high added value.

From the 15th to the 18th century, as the raw material was plentiful, they worked mainly the wood of conifer.

They began to excel at the following fields: The turnery, the white cooperage, the pipe, the toy...

But in spite of the sustainability of the model farmer-craftsman, history came into the mountains: by 1450, a goldsmith called Johannes Gutenberg improved an old Chinese invention: printing.

I was absent from the forum in past year, as I was working for a watchmaking company, for which I was involved in preserving know-how projects.

But I missed my blog activities! I don't feel I am cut off to sit behind a desk, so I created a new website:

www.foudroyante.com/en

Let's talk about watchmaking, without complacency, and also about history and know-how. Here is a condensed version of an article I wrote recently about the Farmer-watchmaker, from 1380 to the beginning of the « glorious thirties ».

In Europe, Roman Empire collapsed by the end of the 5th century, but it left behind a continent more united than ever, using a single language, Latin, and a single religion, catholic Christianity.

This unity led to one of the longest period of deadlock in European history: the middle ages. Its economy was based on the clearance of vast forests that covered the continent. In these conflictual times of relative stability, the population

grew until the end of forest cleaning, in 1280. Contemporary Europe was less wooded than it is today.

Celtic and Gallic agricultural skills had been forgotten and the yields were minor: between 5 and 10 quintals per hectare.

The current productivity in comparison is 80-100 quintals per hectare in intensive and 40-50 in organic. It was only in the 17th-18th century that Europe started its first agricultural revolution, with new techniques of crop rotation, accompanied by forage plants.

Doubling yield were translated into savings on labor, and feeding several generations of scientists. One of them was

Christian Huygens widely regarded as the inventor of modern watchmaking concepts. This will be the beginning of the industrial revolution.

Let us return to the 14th century, the darkest period in Middle Ages history, which unfortunately tends to provoke a skewed vision of that period, yet relatively prosperous and peaceful.

Poor crop yields were hardly sufficient to feed the increasing population. In addition, in the early 14th century, a series of years of drought followed by years of torrential rains caused widespread famine in Europe. Malnutrition was a fertile compost for diseases, especially for the terrible black plague.

The tensions related to the resources led to a war series, in particular the one hundred years war. To finance wars, taxes rose disproportionately, provoking violent jacqueries. It is thus in this particularly dark context that ended the 14th

century.

Imier De Ramstein, Prince-Bishop of Basel was elected in 1382. His bishopric included the Canton of current Jura. Its debt remained huge at that time. Imier made repeated attempts to boost the local economy. In 1384, he published a ery innovative edict: a tax exemption for those who settle 1000 meters above sea level.

Many farmers, by the end of the century, weakened by a hundred years of shortages, diseases and violence, set out to conquer an environment famous to be inhospitable, even hostile.

In the year of our Lord 1384, the Canton of Jura wasn't completely wild, as evidenced by the village of Montfaucon, built in the early 11th century.

However, the nature remained particularly wild, probably unchanged since the last glacial era. Wolves and bears reigned supreme over the fauna. The common point of these species is their adaptability in the conditions of height, thanks to their coat, their muscular power, their overdeveloped vascular network or their large-scale wings. If this fauna prospered, it was because Jura was protected for a long time from the human presence, thanks to a rough microclimate and to a steep topography.

In spite of a modest maximum height (1720 meters), the drafts and the high perched valleys cause very low temperatures during the winter : in the Vallée du Joux, or, even worst, in the vallée de la Brévine, the temperatures

Sometimes dip as low as -40°C.

Nowadays, Jura is divided between Switzerland and France. The wars made the border move, notably during the 30 years war (1618-1648) and also during the Napoleonic wars (1798-1815). The imperial desires of the French autocrats

Sometimes overflowed on the future territory of the Swiss Confederacy, the people from Jura have always shown themselves to be extremely supportive, especially in the Franches-montagnes, where contraband (notably watchmaking) was wisely organized.

But in 1384, our « Franc montagnard » had to become established. As he often does, man changed his environment and farmer-watchmaker ancestors organized vast slash-and-burn, in order to increase the building and arable surfaces.

That is how a multi-thousand-year-old forest of broad-leaved trees disappeared. The inhabitants of Jura planted coniferous trees which push away much faster in extreme montain conditions.

This choice of essences made them precursors of sustainable forestry exploitation. With a view to preservation, fences were forbidden in « Franches montagnes » by the Bishopric of Basel. That explains the presence of these magnificent demarcation low walls in the fields.

It should be pointed out that contrary to common beliefs, until the industrial revolution, serfs in traditional society did not work a lot, three days a week in average. The rest of the time was dedicated to parties or celebrations (religious or not), household activities, collection in the forest, handiwork and wine.

But the farmers of Jura had to work a lot more. In order to gather enough provisions to get through the cruel winter, the brief six month sunny season was a period of intense work. Thus, in the summer time, they had to get up even earlier for long days of agricultural labor: do the transhumance, plant and collect cereals, fruits and vegetables quickly, cut hay, and take refuge with the hearth before the snowfalls. The agro-sylvo-pastoral balance was particularly fragile in such a hostile context. Moderation, patience and precision were essential to the survival mountain farmers. They also needed those virtues for craft sector, and even more for watch-making.

From the beginning of the 15th century, the « Franc-montagnards » farmers knew the torments of contemporary work pattern, with the stress of a "deadline", literally!

At this beginning of the Renaissance, the leisure society was still distant. The future farmer-watchmaker were about to spend their winter time making crafts.

And as the constraint makes the man, they adapted their crafts to logistic constraints, in a typical Darwinian logic. It takes a daytime to walk 15km in the mountains. This difficulty of access weighed against any manufactured product of consequent size, so they specialized in small accessories with high added value.

From the 15th to the 18th century, as the raw material was plentiful, they worked mainly the wood of conifer.

They began to excel at the following fields: The turnery, the white cooperage, the pipe, the toy...

But in spite of the sustainability of the model farmer-craftsman, history came into the mountains: by 1450, a goldsmith called Johannes Gutenberg improved an old Chinese invention: printing.

Comment